How to Help Kids Decide to Spend Less Time Playing Video Games

A 4-step process allows children to come to the conclusion on their own.

How can therapists help their clients understand that they're spending too much time playing video games?

This piece has been featured as an essential topic in Psychology Today.

I stayed up until three in the morning last night playing video games. Accidentally.

I was playing The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, a Lord of the Rings-style adventure game with swords, elves, werewolves, assassins, and dragons. I had intended to play until around midnight, because I could sleep late this morning.

When parents send their children to see me as a therapist, one of their first concerns is often the amount of time the child spends gaming each day.

This is a valid concern; gaming can be time-consuming. Gaming enthusiasts and addicts alike can spend considerable time in front of screens, sometimes at the cost of sleep, homework, social activities, or other hobbies.

Gamers often sacrifice sleep for more time playing video games.

Shen Comix, used with permission.

Unfortunately, directly telling someone to change is not effective and may have the opposite effect. People only achieve real, lasting change when internally motivated. This is the principle behind motivational interviewing, a style of therapy in which therapists help clients identify and prioritize their own reasons for change.

For example, smoking is harmful to one’s health. However, telling a smoker to quit for that reason might simply turn into an argument, which could make the smoker less likely to stop.

In contrast, a motivational interviewing therapist might ask the smoker why they want to quit and encourage the smoker to talk about ways their life would improve without nicotine. That way, the smoker and therapist are on the same “team” against the problem and the smoker is also arguing for change.

So a therapist who advocates to their clients that they should spend less time gaming could actually make them less likely to change.

This is where most parents are when first coming to my office for help. Their family interactions have been reduced to, “Turn off that game and do something else!” followed by, “It’s fine, Mom, all my friends are playing too, you’re being unfair!”

When I meet new clients, I must tread very carefully. If I agree with the parents that gaming time should be reduced, I hurt my chance to build an alliance with the child. However, if I side with the child that their behavior is acceptable, I damage the parents’ trust in me.

Instead, I adopt a neutral stance and work toward establishing objective information on which everyone can agree. Typically, parents and children have wildly different estimates of how much time is spent gaming. We need to start from a common set of facts, and defining the number of gaming hours spent each week is a good place to start.

This is a four-step process:

Step 1: Ask the gamer to estimate how much time they spend every week playing video games and other activities.

I often start this by simply noticing, “It seems like one of the causes of this argument is that you have very different ideas about how much time he’s spending on games.” Then, turning to the client, I ask, “How many hours do you think you play every week?”

I’m flexible with the process of creating this estimate. Some express this in hours per week, while others prefer to estimate by drawing a pie chart or other structure. This initial estimate is important for two reasons: The first is that it is almost certainly inaccurate, as research suggests that people struggle to accurately estimate how much time they spend playing video games. The second is that most gamers are content with their time spent gaming. This may be because they underestimate the actual amount of time they spend.

This step helps assess how much time they believe they spend and establishes a baseline for what they feel is appropriate for themselves.

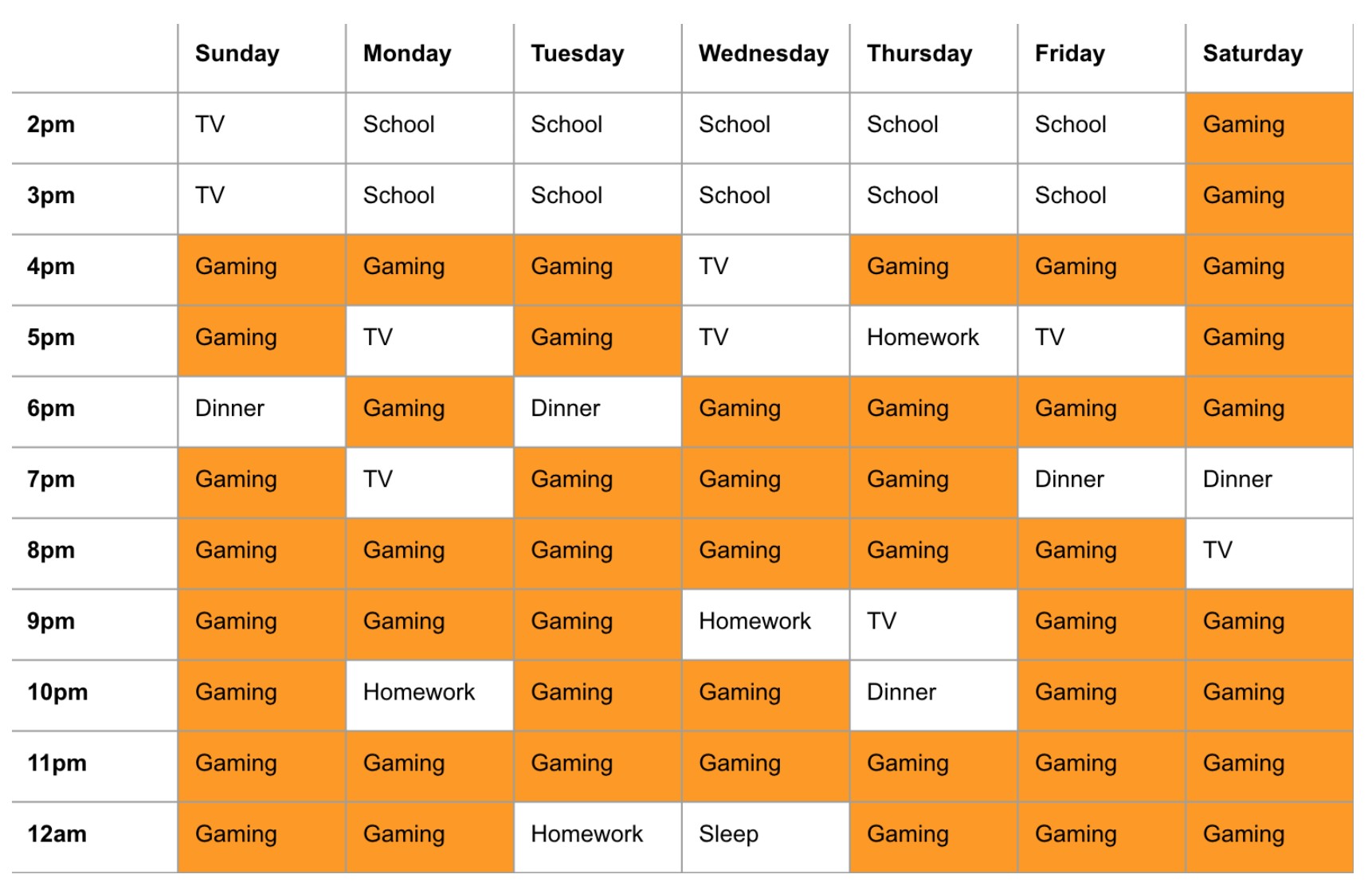

One middle school student named Alexander estimated that he spent his time like this:

Alexander’s estimate of time spent.

(I changed most categories to shades of gray here to highlight time spent gaming in orange.)

Alexander reported that he played video games about eight hours a week: one hour each night, and two hours on Saturdays. He also said that he slept eight hours each night, spent seven hours a day at school, worked on homework about nine hours a week, etc.

Step 2: Accept their estimate non-judgmentally and invite them to test it.

I thanked Alexander for sharing and asked if he would be willing to do an experiment to test it. “It’s funny, a lot of people are way off when they do this. Are you okay keeping track of your time over the next week to see if you were right?” I suspected that the numbers he reported were highly inaccurate, but I knew that he needed to discover this for himself.

He laughed and shrugged, “Sure, why not?” I handed him a blank chart listing the days of the week with twenty-four boxes underneath each, for each hour of the day.

I asked him to spend a few minutes every night logging how he’d spent every hour that day. With his permission, I gave his mother an identical document and asked her to also fill it out with her observations.

When they returned the following week, the two charts looked very similar. I laid both on the table in front of him and asked him to help highlight categories in different colors. This is a section of his estimate, with video games highlighted.

A section of Alexander's chart.

As he started to highlight the “gaming” hours, he was shocked. He had never seen his time visualized like this.

Step 3: Compare the results to the initial estimate.

I then typically sketch a pie chart with the week’s data and lay it next to the original estimate we made the week before. They are easy to compare side by side.

Alexander's estimated and actual use of weekly time spent.

I generally feign surprise at this point. I don’t want to indicate that I did not believe them or that I expected such a large discrepancy. I then ask them what they think about it.

Many parents feel compelled at this point to confront their children with the data. “See? I told you you’re spending all your time in front of that screen.” Obviously, this strategy is likely to have the opposite effect. Confrontation often creates defensiveness. Instead, it is critical to let them interpret the data and help them reach the conclusion themselves.

When handling this step with neutral curiosity, most reach the conclusion that their schedule does not match how they want to spend their time.

I approach this step by simply asking, “Wow, that’s a big difference. What do you think about that?” and encouraging them to reflect. At this point, the client nearly always concludes that they should reduce their time in front of screens.

Step 4: Discuss goals for change.

Once the client has decided that they want to adjust their schedule, I pull out another blank chart. “It seems like what’s happening right now isn’t how you actually want to spend your time. Let’s figure out how much time you’d like to spend on different things each day.”

Typically, my clients set a very reasonable schedule for themselves at this point. Gaming stays on their planned schedule, but is usually reduced to an hour or two per day. Time spent on homework and with friends increases. Time sleeping increases, as they know that they should be going to bed earlier. Some even add after-school activities.

At this point, my client, their parents, and I are all working toward the same goal, which the client is internally motivated to achieve. Making this adjustment will be challenging, but now everyone is on the same team, making success more likely.